closing the culture gap

Jason Robert LeClair

Closing the Culture Gap Synopsis

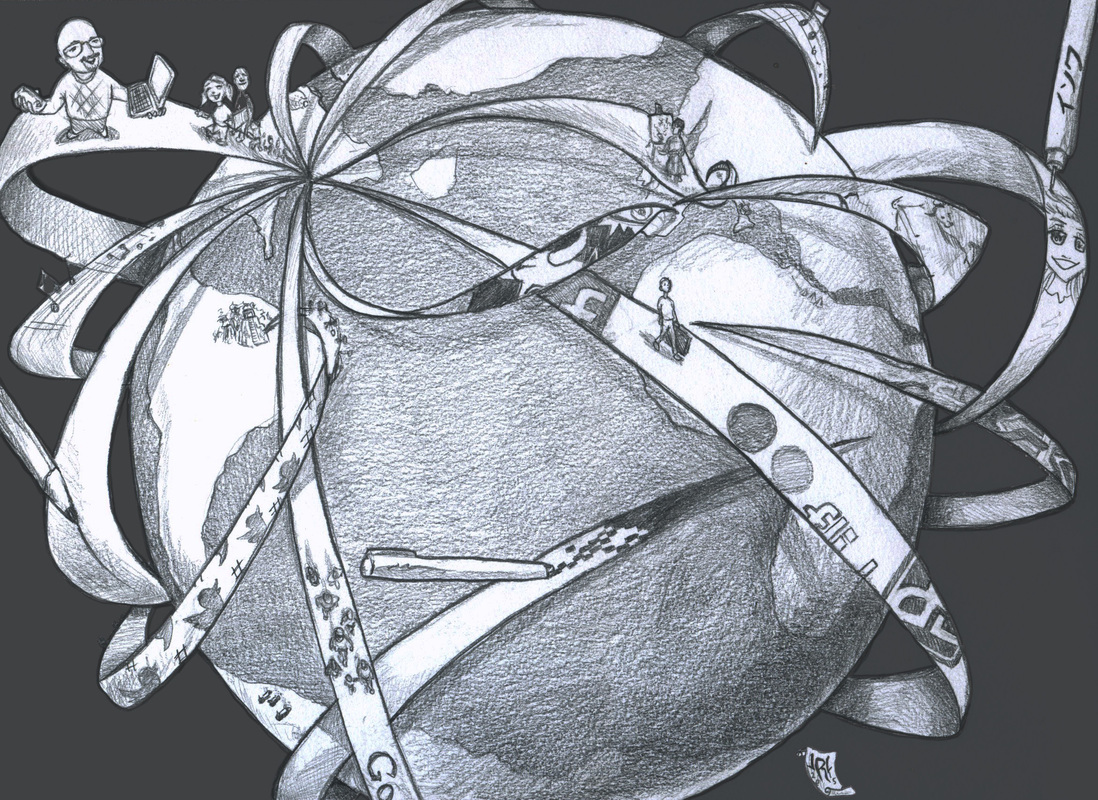

In analyzing readings from Globalization, Art, and Education with Dr. Delacruz, I have found one topic that weaves throughout; culture and students’ different approaches to the concept of culture, in particular, how it pertains to art. The work I am presenting is made with the encouragement of exploration and experimentation in mind, using the social media tools at our disposal. As lead learner and fellow explorer, I guide my students on this global trek.

Closing the Culture Gap Synopsis

In analyzing readings from Globalization, Art, and Education with Dr. Delacruz, I have found one topic that weaves throughout; culture and students’ different approaches to the concept of culture, in particular, how it pertains to art. The work I am presenting is made with the encouragement of exploration and experimentation in mind, using the social media tools at our disposal. As lead learner and fellow explorer, I guide my students on this global trek.

Jason Robert LeClair

ARE:6933 Globalization, Art, and Education

Dr. Elizabeth Delacruz

Closing the Culture Gap

Mind the gap: the culture gap. Said gap is closing as far as international and national ideals are concerned. Is art education helping? Let us first take a look at just what it is that arts education does. According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, “ Such education not only strengthens cognitive development and the acquisition of life skills…. But also enhances social adaptability and cultural awareness for individuals…” (para. 3). It goes on to say that the overall cultural implications of arts education expand tolerance of differences as well as providing positive societal ramifications. These include but are not limited to “social cohesion” and “preventing standardization and promoting sustainable development” (para. 3).

Art movements seep their way into popular culture and the students we have in class are the ones who latch onto this. Though popular culture is often seen as less than fine art, there are artists whom use it as the key to their work. Since the Pop Art movement and the acquisition and adaptation of popular images with Andy Warhol, we have seen the use of our American culture in fine art around the globe. Jeff Koons, a contemporary pop artist, takes and creates images in two and three dimensions derived from items of popular culture of the United States. His paintings are large reproductions of his digital montages using themes from larger cultural contexts with societal significance and wrapping them with images of popular icons (Art21, 2009). Artist Takashi Murakami is noted for his work with both Japanese and western cultural traditions blended in his “superflat” work (The Creator’s Project, 2013). Both of these artists take from the consumer culture of their nations and produce works that become highly significant to the fine art world. Koons, using appropriated images, and Murakami using a mix of styles and genres with his original content.

Where, then does the culture gap occur for our students? In the building of social networks around common interests via the internet, students cross, or rather circumvent the borders of face-to-face communication forming groups of online communities with common interests (Delacruz, 2009). The boundaries enacted by social status are also partially set aside through online social networks centered around common arts interests. Take, for example, the communities of fandoms across the globe. According to Manifold (2009), these individuals (mostly adolescents ages 13 – 24) commune about topics of their favorite fantasy fiction characters and stories. Taking the popular narratives of comic books, Japanese Manga/Anime, Disney, or a myriad of other popular characters, these fans will create derivative works (fanart), and/or costumes (cosplay), and reimagine themselves within the worlds of these characters (2009). This escapism creates a culture onto itself with its own set of societal rules and behaviors. As a parent of cosplayers, and a sometime participant in the convention culture, I have observed the complexities of communal interactions of these fans. There are particular societal rules that set expectations for participation. These rules, if broken, are a cause for community retaliation. Whether it is a group shunning, or social media outrage over the offense, the society is self-policed. These communities, however, are generally escapism for the participants and frequently remove them from real-world issues that are in need of their creative energies to effect change (Manifold, 2009). This, in effect widens the gap.

It is our task as arts educators to tap into this and not redirect, but guide students to fuller understandings of life and society through their personal interests. The cross-cultural abilities that things like visual literacy provide is a great starting point for such ventures. In providing the guide for student learning, we must first open ourselves up to being model learners. In her blog, Gerstein (2015), states, “To effectively do so, though, the educator needs to understand and be able to articulate and demonstrate the process of learning, him or herself.” In this way, educators lead by example creating an environment of inquisitive learning methodology versus rote learning through imitation (Gerstein, 2015). Using this principle along with the concept of visual literacy, we inspire something. As was pointed out by Lin in association with the use of technology and social media, “education scholars and policy makers overlook the richness and unpredictability of inquiry which I believe to be central in the process of learning in any domain” (2009). This learning is central to the arts, wherein mistakes and failures are a necessary part of the artistic process. Teachers need to show that we too are fallible. The key is to use such failures as examples more concrete than from a book. This lowers the expectation for perfection on the first try, something that I see in the classroom everyday. There is a need for students to make highly polished work from the onset as their source for artistic inspiration is derived from the highly polished commercial art world, which they long to emulate. I have the fortunate ability to have many friends in the industry (game designers, animators, graphic designers, illustrators) who have agreed to share their work and more importantly, their process with my students. This has put a real world context into artwork for my students.

Process is the key to what we do in the arts. The journey to our final product is even more important than the finalized work. Like the artists highlighted above, the beauty of the work is in the making of it. Murakami explores his heritage and his present as well as studying the methodology of both Japan and Europe/U.S. artists to enhance his cultural impact. Koons delivers the next generation of Warhol’s factory in his studio practices. It is important for the students to understand the nature of how these things come to be, that in defining the culture of our world and closing/bridging societal gaps, they must first explore the wider global landscape that becomes ever more accessible through technology.

Resources

United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Association. (2014). Arts Education. Retrieved from

http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/creativity/arts-education.

Delacruz, E. M. (2009). From bricks to mortar to the public sphere in cyberspace: Creating a culture of caring on the digital global commons. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 10(5). Retrieved from http://www.ijea.org/v10n5/index.html

Lin, C. (2009). Beyond visual literacy competencies: Teaching and learning art with technology in the global age. In E. M. Delacruz, A. Arnold, M. Parsons, and A. Kuo,

(Eds.), Globalization, art, and education (pp. 198-204). Reston, VA: National Art Education Association.

Manifold, M. C. (2009). Creating parallel global cultures: The art-making of fans in fandom communities. In E. M. Delacruz, A. Arnold, M. Parsons, and A. Kuo,

(Eds.), Globalization, art, and education (pp. 171-178). Reston, VA: National Art Education Association.

Murakami, T. (2013). The Creator’s Project. Takashi Murakami on Jellyfish Eyes, Nuclear Monsters, and Artistic Influences. May 29, 2013 Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sJEmGM1JS7k

Koons, J. (2009). Art21. Fantasy. PBS October 14, 2009. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/art21/watch-now/segment-jeff-koons-in-fantasy

Gerstein, J. (2015). User Generated Education. Educators and Lead Learners. February 16, 2015. Retrieved from

https://usergeneratededucation.wordpress.com/2015/02/15/educators-as-lead-learners/

ARE:6933 Globalization, Art, and Education

Dr. Elizabeth Delacruz

Closing the Culture Gap

Mind the gap: the culture gap. Said gap is closing as far as international and national ideals are concerned. Is art education helping? Let us first take a look at just what it is that arts education does. According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, “ Such education not only strengthens cognitive development and the acquisition of life skills…. But also enhances social adaptability and cultural awareness for individuals…” (para. 3). It goes on to say that the overall cultural implications of arts education expand tolerance of differences as well as providing positive societal ramifications. These include but are not limited to “social cohesion” and “preventing standardization and promoting sustainable development” (para. 3).

Art movements seep their way into popular culture and the students we have in class are the ones who latch onto this. Though popular culture is often seen as less than fine art, there are artists whom use it as the key to their work. Since the Pop Art movement and the acquisition and adaptation of popular images with Andy Warhol, we have seen the use of our American culture in fine art around the globe. Jeff Koons, a contemporary pop artist, takes and creates images in two and three dimensions derived from items of popular culture of the United States. His paintings are large reproductions of his digital montages using themes from larger cultural contexts with societal significance and wrapping them with images of popular icons (Art21, 2009). Artist Takashi Murakami is noted for his work with both Japanese and western cultural traditions blended in his “superflat” work (The Creator’s Project, 2013). Both of these artists take from the consumer culture of their nations and produce works that become highly significant to the fine art world. Koons, using appropriated images, and Murakami using a mix of styles and genres with his original content.

Where, then does the culture gap occur for our students? In the building of social networks around common interests via the internet, students cross, or rather circumvent the borders of face-to-face communication forming groups of online communities with common interests (Delacruz, 2009). The boundaries enacted by social status are also partially set aside through online social networks centered around common arts interests. Take, for example, the communities of fandoms across the globe. According to Manifold (2009), these individuals (mostly adolescents ages 13 – 24) commune about topics of their favorite fantasy fiction characters and stories. Taking the popular narratives of comic books, Japanese Manga/Anime, Disney, or a myriad of other popular characters, these fans will create derivative works (fanart), and/or costumes (cosplay), and reimagine themselves within the worlds of these characters (2009). This escapism creates a culture onto itself with its own set of societal rules and behaviors. As a parent of cosplayers, and a sometime participant in the convention culture, I have observed the complexities of communal interactions of these fans. There are particular societal rules that set expectations for participation. These rules, if broken, are a cause for community retaliation. Whether it is a group shunning, or social media outrage over the offense, the society is self-policed. These communities, however, are generally escapism for the participants and frequently remove them from real-world issues that are in need of their creative energies to effect change (Manifold, 2009). This, in effect widens the gap.

It is our task as arts educators to tap into this and not redirect, but guide students to fuller understandings of life and society through their personal interests. The cross-cultural abilities that things like visual literacy provide is a great starting point for such ventures. In providing the guide for student learning, we must first open ourselves up to being model learners. In her blog, Gerstein (2015), states, “To effectively do so, though, the educator needs to understand and be able to articulate and demonstrate the process of learning, him or herself.” In this way, educators lead by example creating an environment of inquisitive learning methodology versus rote learning through imitation (Gerstein, 2015). Using this principle along with the concept of visual literacy, we inspire something. As was pointed out by Lin in association with the use of technology and social media, “education scholars and policy makers overlook the richness and unpredictability of inquiry which I believe to be central in the process of learning in any domain” (2009). This learning is central to the arts, wherein mistakes and failures are a necessary part of the artistic process. Teachers need to show that we too are fallible. The key is to use such failures as examples more concrete than from a book. This lowers the expectation for perfection on the first try, something that I see in the classroom everyday. There is a need for students to make highly polished work from the onset as their source for artistic inspiration is derived from the highly polished commercial art world, which they long to emulate. I have the fortunate ability to have many friends in the industry (game designers, animators, graphic designers, illustrators) who have agreed to share their work and more importantly, their process with my students. This has put a real world context into artwork for my students.

Process is the key to what we do in the arts. The journey to our final product is even more important than the finalized work. Like the artists highlighted above, the beauty of the work is in the making of it. Murakami explores his heritage and his present as well as studying the methodology of both Japan and Europe/U.S. artists to enhance his cultural impact. Koons delivers the next generation of Warhol’s factory in his studio practices. It is important for the students to understand the nature of how these things come to be, that in defining the culture of our world and closing/bridging societal gaps, they must first explore the wider global landscape that becomes ever more accessible through technology.

Resources

United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Association. (2014). Arts Education. Retrieved from

http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/creativity/arts-education.

Delacruz, E. M. (2009). From bricks to mortar to the public sphere in cyberspace: Creating a culture of caring on the digital global commons. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 10(5). Retrieved from http://www.ijea.org/v10n5/index.html

Lin, C. (2009). Beyond visual literacy competencies: Teaching and learning art with technology in the global age. In E. M. Delacruz, A. Arnold, M. Parsons, and A. Kuo,

(Eds.), Globalization, art, and education (pp. 198-204). Reston, VA: National Art Education Association.

Manifold, M. C. (2009). Creating parallel global cultures: The art-making of fans in fandom communities. In E. M. Delacruz, A. Arnold, M. Parsons, and A. Kuo,

(Eds.), Globalization, art, and education (pp. 171-178). Reston, VA: National Art Education Association.

Murakami, T. (2013). The Creator’s Project. Takashi Murakami on Jellyfish Eyes, Nuclear Monsters, and Artistic Influences. May 29, 2013 Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sJEmGM1JS7k

Koons, J. (2009). Art21. Fantasy. PBS October 14, 2009. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/art21/watch-now/segment-jeff-koons-in-fantasy

Gerstein, J. (2015). User Generated Education. Educators and Lead Learners. February 16, 2015. Retrieved from

https://usergeneratededucation.wordpress.com/2015/02/15/educators-as-lead-learners/

| leclair_globalresearch.pdf | |

| File Size: | 98 kb |

| File Type: | |